True Magic or Real Magic

True and Real Magic are two different things.

True = subjective

shared subjective truths can seem like realities.

Real = what the subject cannot make true or false and simply is

Real is True True, and doesnt fail when exposed to nature in all its forms.

strive for da true true...

we'll leave you with some disconnected connected transmissions:

Meandering words / signaling disconnected but gatewayed:

there's some writing written in the past (or 10-20 years back), that got preserved but never manifested:

ha, twitter and facebook, have you met ghosters?

written genres are alot like different cultures coinage. Picaress your interests wisely.

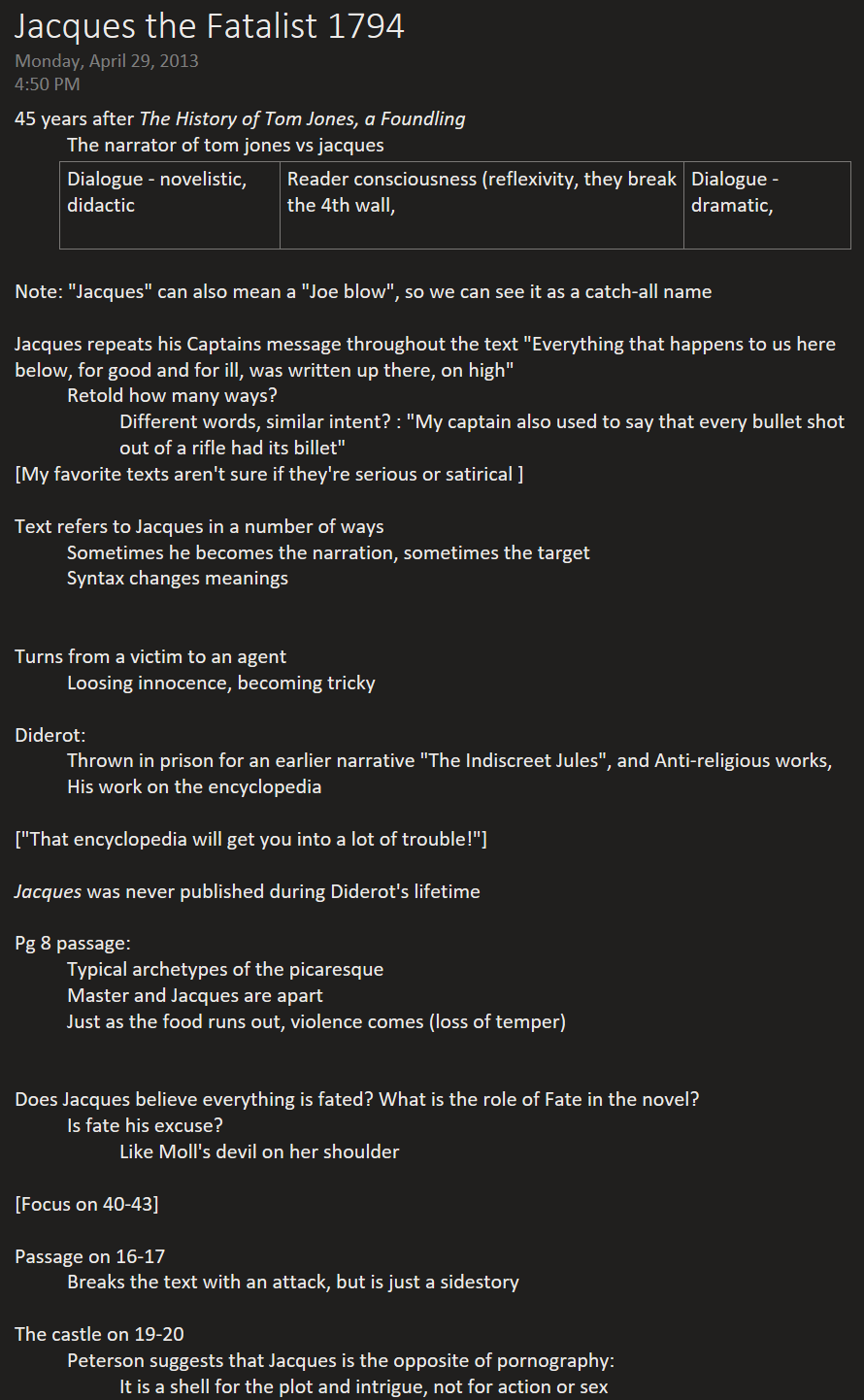

Jacque and Sömme Guy (me) arent too dissimmilar so lets review some notes on the fatalist;

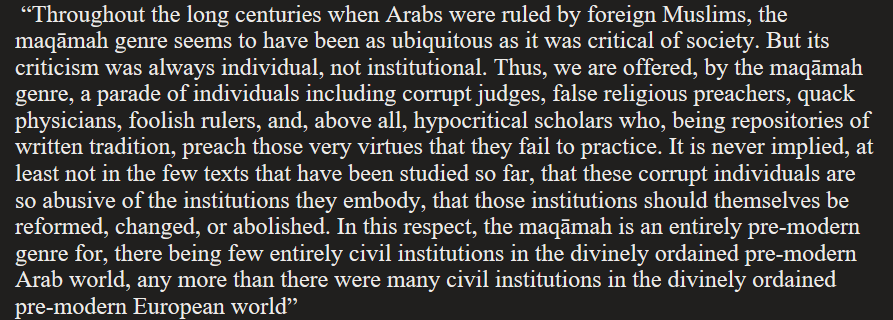

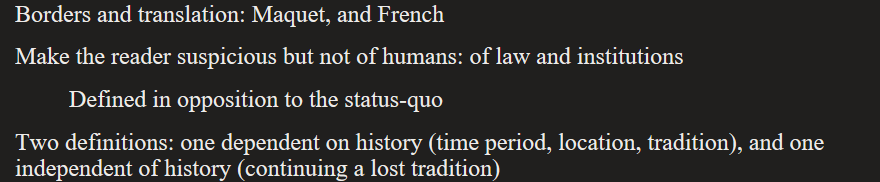

but western lit just copied whst was already there: maqāmah. apoken word tales, lost to low fidelity and re-coinage.

back to europeeins:

Defining the Picaresque: Different Way to use a Two-Faced Coin

5/3/13

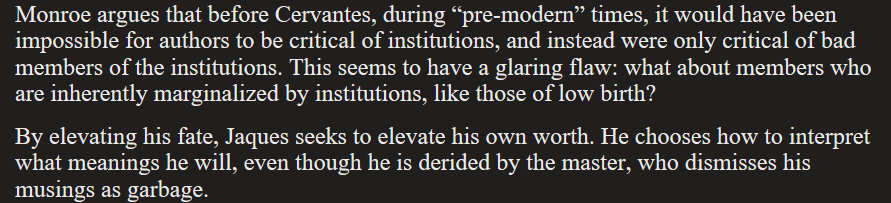

Attempting to define a genre is like trying to separate coins: the result of the separations will differ depending on how the coins (i.e. works or novels) are scrutinized. The separator picks arbitrary rules and applies them methodically to the task of separation. How should the picaresque be distinguished from other genres? The most severe definition of the picaresque maintains that the picaresque classification should be strictly limited to only a few works written in the Spanish language spanning the time between the anonymously published 1554 Lazarillo de Tormes and Francisco de Quevedo’s 1626 The Swindler, because these novels arose in relationship to the rise in usage of the Spanish root word, picaro. Although the previously named works unquestionably arose from shared historical, cultural, and religious contexts and share similar settings, characters, and predicaments, the way each text characterizes those contexts and their formal goals are quite different if not completely opposed. The discernible differences between the works may be a part of why the “picaresque” classification has been applied to novels that follow in some traditions of these works, even though they lack the immediate connections to the historical and etymological origins of the most severe definition. What classifies a work as primarily picaresque rather than subordinately picaresque? So, how should the picaresque novel be defined if we want to expand the barriers of the picaresque classification to include works such as Denis Diderot’s 18th Century Jacques the Fatalist? In James T. Monroe’s study of the maqāmah, a Middle Eastern genre, he describes the maqāmah genre as “one branch, and a very important one at that, of the picaresque genre” (Monroe, 2). His analogy for the picaresque genre as a tree seems a bit strange, as the seed word, picaro, had not yet been planted when the maqāmah texts were created and developed in the 11th and 12th centuries. Perhaps we can exchange Monroe’s “picaresque” tree and branch analogy for a coin analogy to better form a definition which can span countries and times: the picaresque genre is not a coin of a specific shape/size belonging to a specific time or place, but a counterfeit two-faced coin. Counterfeit, in the sense that it is not designed to be taken as “genuine” when we are close to it (i.e. reading it with careful observation); it constantly shows signs that it does not fully belong to other genres. Two-face, in the sense that it is not made with the intention of functioning like a more traditional genre would. When the recipient of the work only sees one side (i.e., an excerpt of the work), they may expect it to behave like another coin (i.e., genre) of its time, but when the recipient see its reverse they are forced to realize that what they thought was genuine may not be. In other words, the picaresque genre is intentionally crafted as something which may resemble parts of other genres of the period, but clearly is not once we know that there is no reverse side to the coin but only two obverse sides[1]. First, by comparing the origins of the maqāmah and the early Spanish picaresque works, we will expand on the two-faced coin analogy discuss how the two-faced coin can been wielded to produce primarily rather than a subordinately picaresque work. Then, we will show how Diderot’s text wields the picaresque coin to produce a primarily picaresque work. We will conclude by observing some of what is gained and lost in this description of the picaresque.

There are a number of interesting parallels to the early Spanish picaresque works that we can form through a cursory exploration of Monroe’s introduction to the Maqāmah texts. Monroe tells us that Al-Hamadani, the writer of the foundational maqāmah work, claimed to have Arab ancestry despite his surname’s indication that he was from the Persian city Hamadhan. Similarly Lazarillo de Tormes’ protagonist Lázaro hints at mixed ancestry. He starts the text by stating that he is the son of “Tomé Gonzáles”. So why is his last name not Gonzáles? Lázaro tells the reader that since he was born in the river Tormes he “took that surname and this is how it all happened” (Alpert, 5). The “this is how it all happened” implies that his story will reveal why his name is different, but he never does. Presumably the “Honour” that the text addresses would be interested in Lázaro’s heredity but nowhere in the text does Lázaro explain why he did not take his father’s surname. Although the text is titled Lazarillo de Tormes, the protagonist is only identified as Lázaro, even as a child. The internal, Lázaro, identity of the text negates the diminutive nature that the title Lazarillo name suggests; the titles initial diminishment is not recognized within the text. We are expecting to hear a story told by a diminutive Lazarillo, but instead receive a veiled text which never distinguishes the reality of the As such we are not able to reconcile the identity of the narrator with his narration. All of these bits of misinformation evidence a contradiction in what we are told and what we should believe. Since there is nothing to distinguish the identity of the preface of Lazarillo de Tormes from its author we cannot fully reconcile the world of the work as purely fictitious. This type of narration creates an unbroken inequality between the narrator and what is being narrated. Conversely, The Swindler’s narrator is separated from the identity of the author of the text by a preface which advertises the following pages as an interesting fiction of a character who Quevedo calls “my delightful Don Pablos, Prince of the Low Life.” (Alpert, 63). When the writer of Lazarillo de Tormes wrote his work, he was not trying to create a genre, he was simply crafting a fiction in opposition to commonly accepted genre forms of the time. Quevedo’s text was not formed with the same type of opposition and merely reused the forms which made Lazarillo de Tormes popular. By borrowing from the innovations of Lazarillo de Tormes, and acknowledging them, Quevedo separates his authority from fictional text’s authority and makes the reader certain that they are dealing with a deceitful coin, whereas Lazarillo de Tormes can be seen as simply the two-header coin, unmediated by the author. This is the difference between subordinately picaresque works vs. primarily picaresque works. Quevedo’s is exemplary of a subordinate picaresque because it reveals the trick of the picaresque explicitly, while Lazarillo does not. To use the coin analogy, Lazarillo de Tormes never explicitly states that we are being tricked by the coin, while Quevedo’s text explicitly makes clear that what we read is a playing with the trick coin. Monroe suggests a similar disconnect between the two seminal maqāmah works

The primarily picaresque texts are written by authors who never want you to believe that what you are reading is a real coin, while the subordinate picaresque works authors have less at stake and do want you to buy their fake coin.

In the texts where the author presents themselves as someone to be trusted external to the world of the text, the reader loses some of the thrill that one receives from trying to identify where the narration One imitating the other, one creating a new coin.

This is an interesting connection because Al-Tjkdhsd and Lazarillo are *** years apart, and in differing countries. We can see Monroe’s attempt to define the maqāmah genre as trying to separate coins for use as legal tender: the resultant separation might be simple and overlook complications. I suggest that the picaresque is a

As in Lazarillo de Tormes, there is no prefatory materials in Jacques the Fatalist to ease the reader into the text. The author’s identity is shielded and all we are given is the world the text creates for us.

Bibliography

Alpert, Michael, and Francisco De Quevedo. Lazarillo De Tormes: And, Francisco De Quevedo : The Swindler (El Buscón) : Two Spanish Picaresque Novels. London: Penguin, 2003. Print.

Diderot, Denis, and David Coward. Jacques the Fatalist. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Monroe, James T. Al-Maqāmāt Al-luzūmīyah. Leiden: Brill, 2002. Print.

[1] In this analogy I do not want to assume that the two sides are identical, but rather that the wholeness of the faked genre is fractured. E.g., Lazarillo de Tormes tries to present itself as a truthful narrative being brought to light by its narrator, but by its end wants us to recognize that it has actually hidden the truth from us rather than exposed it. “Two-faced coin”, (rather than a more common naming such as “double-headed coin” or “two-headed coin”) is chosen to describe the picaresque because we want to evoke the “double-dealing” and “deceitful” meanings of the adjective “two-faced”.

That essay snippet is only a blip in the ocean. critize the individual, which now can also classify itself as institution (law is weird... a company can be "a person"?)

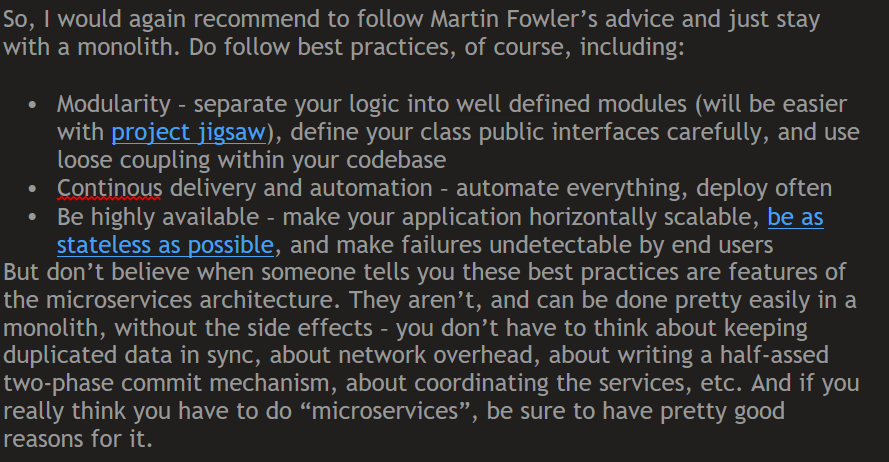

from 2015 article by https://techblog.bozho.net/:

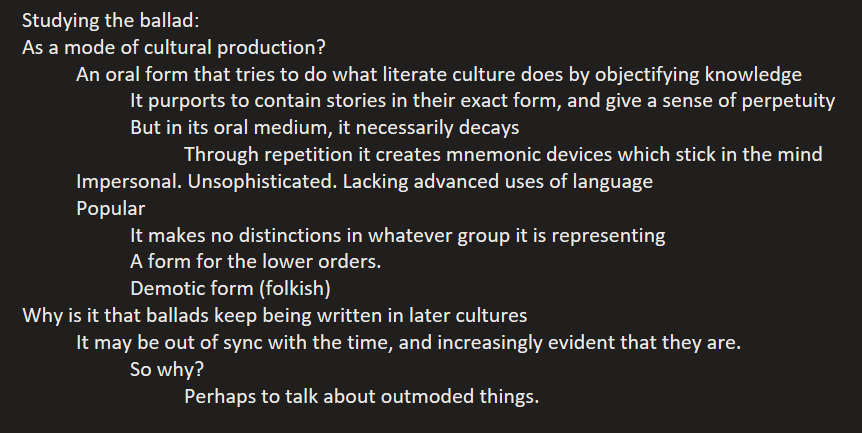

sing the songs, not just only repetative ballads.

Enjoy your sea shantys, but remember some just ape tradition, while others innovate on the genre.

listen to both ok... if you must... (theres better music folks), but the inventive ones that reveal the cracks in time and apespace are the ones to listen to on repeat, until they become outnoded.

create sustainable joys and pleasures for mankind, not just strange genre adaptations of skinner-boxes

Member discussion