Why I Call Myself a Malcontent

I will tell you the way I see the world, and it’s quite possible you’ll agree; it’s also possible that you’ll only somewhat understand, but you can’t tell me I’m completely wrong without having denied my mind it’s happy existence.

Life is indulgence. Anyone who tells you that you are acting self-indulgent is true. Telling yourself you are being self-indulgent is a lie, because you are trying to distinguish that action from your life. Life is indulgence. Doing is a privilege. Go and indulge yourself however you choose.

You don’t own anything. I do not mean that ownership does not exist; it is simply an idea, a self-indulgence within human life. I base my life upon these notions.

Most people’s perceptions are vastly skewed from how the world exists, and would vehemently argue me here. I would agree with many of their statements, but some perceptions I would disagree with, and fight, following the beliefs I laid out above. I would eventually be called a misanthrope by some mistaken charlatan.

I would tell them that I am a malcontent, not a misanthrope. Call me maladjusted, malnourished, malformed, malfunctioning; call me for a good Malbec, but do not call me a misanthrope, for I am not a hater of man.

“How can one exist once they believe they own nothing?”: with fear and gratitude, awareness that their solitude is real and awareness that existence is meaningless, until you impose meaning. This imposition is a wonderful thing, and it makes you human. Life is self-indulgence.

Investments impose feelings of external meaning, and are worthwhile when they go according to plan.

Doing nothing will leave you frustrated after observing other people enjoy their self-indulgence.

So go out and do and be and live… if that’s what you’d like to do.

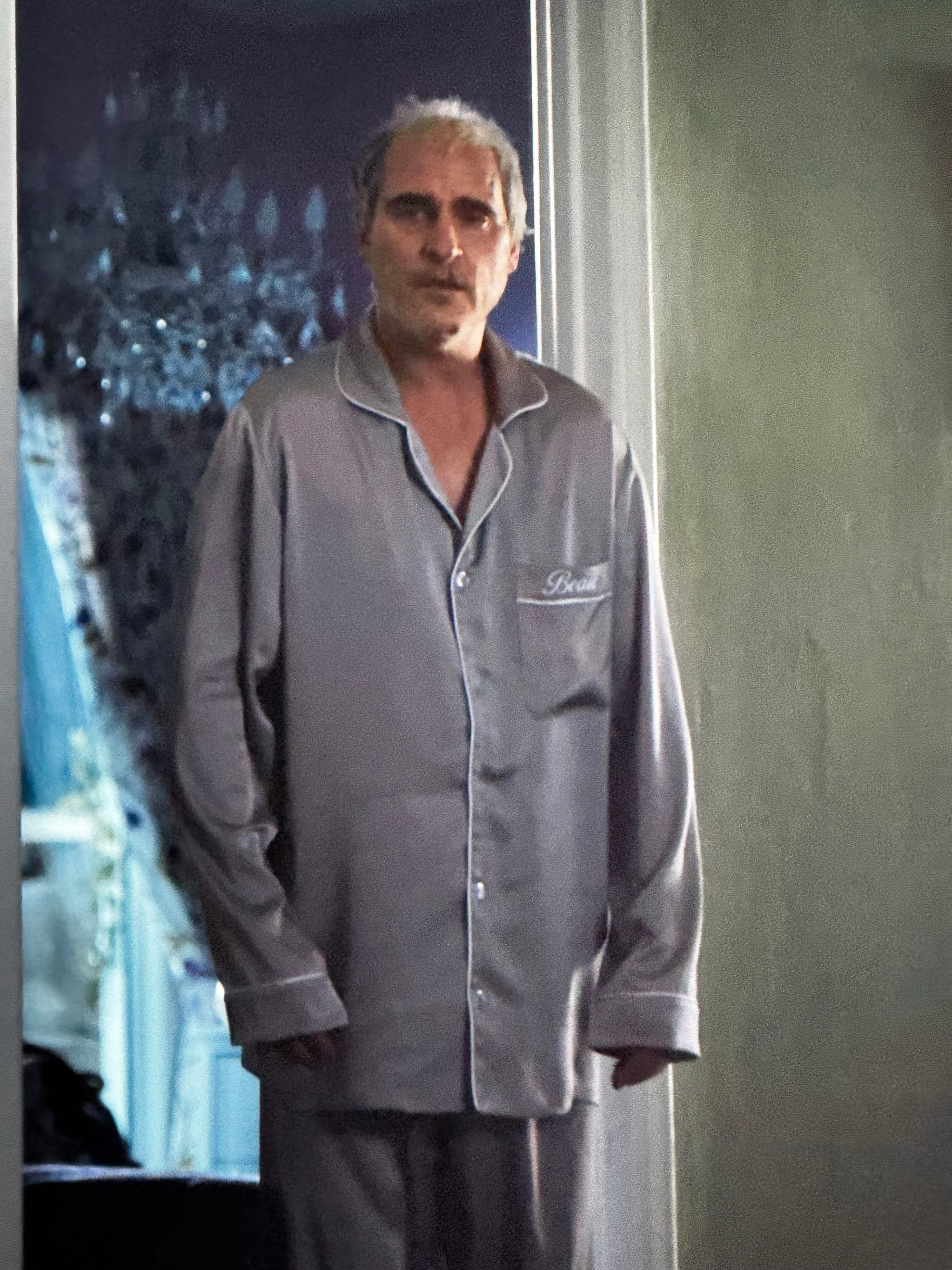

Beau review:

Ari Aster's "Beau is Afraid" is a surreal and thought-provoking film that takes viewers on a transformative journey through the life of its protagonist, Beau. Divided into five distinct acts, the film explores the complexities of mental health, the lasting impact of childhood trauma, and the intricate relationship between a mother and her son.

The film opens with Beau's birth, a scene that sets the stage for the pervasive sense of dread and anxiety that will come to define his life. From there, we follow Beau through a series of reality-altering events, each one serving as a catalyst for a new phase in his psychological journey.

A car accident propels Beau into a nightmarish suburban landscape, while a frantic run through the woods and a knock to the head blur the lines between reality and fantasy. These shifting environments, from the grim urban sprawl to the surreal wilderness populated by wandering performers and vagabonds, serve as powerful metaphors for Beau's inner turmoil and the fragmented nature of his psyche.

As the story unfolds, Beau grapples with the realization that he is a character within his own story, a revelation that adds a meta-theatrical layer to the narrative. This breaking of the fourth wall forces both Beau and the audience to question the nature of identity and existence.

Throughout the film, Beau's relationships with his family members, particularly his mother and absent father, are explored through a series of dreamlike sequences and imagined encounters. The revelation that his sons are merely figments of his imagination underscores the depth of Beau's longing for connection and purpose.

In a pivotal scene, Beau attends his mother's funeral, arriving just as the Jewish catering staff is cleaning up. There, he encounters Parker Posey's character, with whom he shares a brief but intense connection. This encounter, marked by a mix of yearning and fear, culminates in a surreal and ultimately tragic moment that serves as a turning point in Beau's journey.

As Beau confronts his mother about the secrets of his past, he finds himself descending into a nightmarish realm populated by monstrous figures and unsettling revelations. This descent into the depths of his psyche is a powerful metaphor for the way in which trauma and repressed memories can resurface, forcing individuals to confront the darkest aspects of their being.

In the film's climax, Beau finds himself on trial in a surreal courtroom setting, his life laid bare before a judgmental audience. This sequence serves as a commentary on the way in which society often stigmatizes and condemns those who struggle with mental illness, reducing their complex experiences to a spectacle for consumption and entertainment.

Ultimately, "Beau is Afraid" is a deeply personal and cathartic work by Ari Aster that explores universal themes of fear, trauma, and the search for meaning in a chaotic world. While the film's focus on a Jewish protagonist and his relationship with his mother may seem specific, Aster's masterful storytelling ensures that the film resonates with audiences from all walks of life.

By delving into the darkest recesses of the human psyche and exposing the raw, unfiltered emotions that reside there, "Beau is Afraid" achieves a level of universality that transcends cultural and demographic boundaries. It is a film that invites viewers to confront their own fears, to empathize with those who struggle with mental health issues, and to recognize the lasting impact of childhood experiences on our adult lives.

Member discussion